With Styled Words

With styled words, alliterate and rhymed,

With syntax smooth and elegance of phrase,

With meter straight, ten syllables per line,

With wink and bow, with chocolates and bouquets

Some men might seek your eye’s enamored gleam,

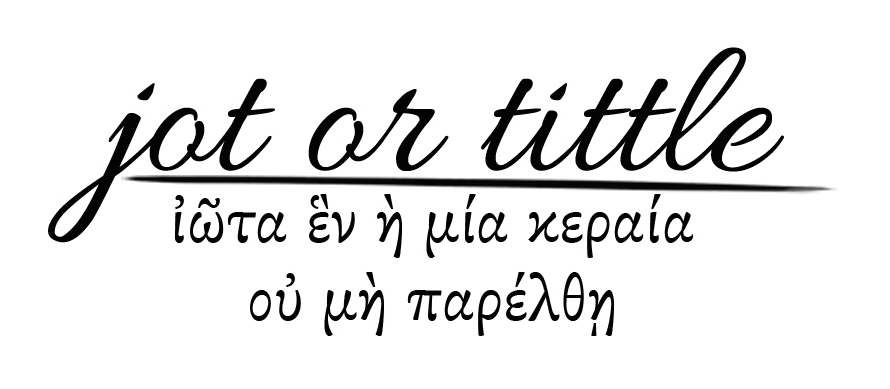

But not I. What they’ve missed I know for true:

That words are cheap and seventy short beats

Deficient here. Such love falls short of you.

The fathers, flawed as we, knew love through tears.

For Rachel loved and Leah despised were asked

Not fourteen lines of ten but fourteen years

With pasture, water, beast, and robber tasked.

A faithful work bears fruit, but words are weeds.

A man’s true love is proven in his deeds.

I wrote this poem as one piece within a short collection for Katy on Valentine’s Day of 2018. Katy asked me to write her a love poem for Valentine’s Day because, despite being on a recent poetry kick, I hadn’t written anything for her.

I ended up writing a short story in the form of a dialogue. One voice asks for a love poem; the other resists or writes drivel, like this haiku:

For you I’d do it

Even though it’s hard

To count syllables.

That is, to say the least, not very good. But it fits the story.

The sonnet above is the capstone to the second voice’s resistance. It’s a fully formed, metered poem refusing to acquiesce to the demand to create art. It does this by deflecting. As such, the message is not a fantastic one. “Word’s are cheap” has its place, but I’m the sort of person who hordes words more often than I should, which is why my wife had to ask me to write her a poem instead of getting one without asking.

The short story has a final poem that actually does express love through words (as best I could manage it). For some reason, though, I like this one better. Maybe I’m partial to sonnets. Maybe I’m just impenitent.

I enjoy the form of sonnets. I like to try to fit an idea into the rigid structure provided by the meter and rhyme scheme, and I like the new ideas the arise as the old, bad ones fail to fall within the lines. Even when I get something that can be called a sonnet, it takes some work to smooth things out. You can’t simply replace a word without throwing everything off balance, which makes revisions challenging—in a good way!

I don’t have my handwritten drafts, but my first digital version ended like this:

The Fathers, flawed as we, knew love through tears.

For Rachel loved and Leah despised were asked

Not fourteen lines of ten, but fourteen years,

Which seemed but days when all had come to pass.

Don’t trust in piled words to meet your need.

A man’s true love is proven in his deeds.

“Seemed but days” fits the biblical allusions (Gen 29:20) and is suitably romantic, but it didn’t really fit with the theme of the poem. It felt like too easy a reach anyway. The line that replaced it, With pasture, water, beast, and robber tasked, has more of a sweat-of-your-brow feel and adds the internal rhyme of “water” and “robber.” It follows “tears” much better.

What are “piled words”? And why would anyone trust them? I don’t know. I needed to rhyme something with “deeds,” which I thought meant I had to get to “needs.” Perhaps there was a better way to get there, but I didn’t think of it.

The final version I gave to Katy ended with this couplet:

Where’er you look, words will spring up like weeds.

A man’s true love is proven in his deeds.

That’s better than the first couplet, but I still don’t really care for it. I have the feeling that it’s a lazy habit to punch syllables out of words with apostrophes. Besides, the only words in the first line doing any real work are “like weeds.”

Here’s the version I’ve shared above:

A faithful work bears fruit, but words are weeds.

A man’s true love is proven in his deeds.

I’m still not quite satisfied. I don’t think it’s catchy enough. I want a couplet to go away with me and make me think about it. If this one goes with me, it will just annoy me. Or perhaps I haven’t been focusing enough on the second line? Feel free to offer your advice or alternatives.

To speak more positively, my favorite part of this poem, and the reason I’m so partial to it, is the line Not fourteen lines of ten but fourteen years. That goes with me. And I think it’s a good payoff for what comes before. There’s something satisfying about a piece of art that undermines itself.

I worry, though, that many people who read it won’t get the meta reference because they haven’t written a sonnet since the seventh grade, and then only under coercion.

Other Poems

-

2021

- Aug 15, 2021 The Lord, the Lord

- Feb 6, 2021 What Paul Said to the Corinthians

-

2020

- Aug 8, 2020 For My Dog

-

2019

- Nov 8, 2019 because

- Nov 1, 2019 When I Say It

- Oct 22, 2019 What I'm Feeling

- Jun 27, 2019 Rushing Light

- Jun 20, 2019 Genesis 37:25

- Jun 7, 2019 At Thirty

- Mar 4, 2019 The End of Wisdom

- Feb 25, 2019 With Styled Words

- Feb 18, 2019 Stargazing at Hartley Springs