God's Good World

My historical theology course with Dr. Adam Nigh was one of my favorites at Fuller Seminary, if for no other reason than that Dr. Nigh introduced me to some of the best secondary literature I read as a seminary student. This week I am adapting a review I wrote of my second favorite book from that course: God's Good World by Jonathan Wilson.

In God's Good World, Jonathan Wilson is adamant that a strong doctrine of creation must shed the modern preoccupation with Genesis 1–2.

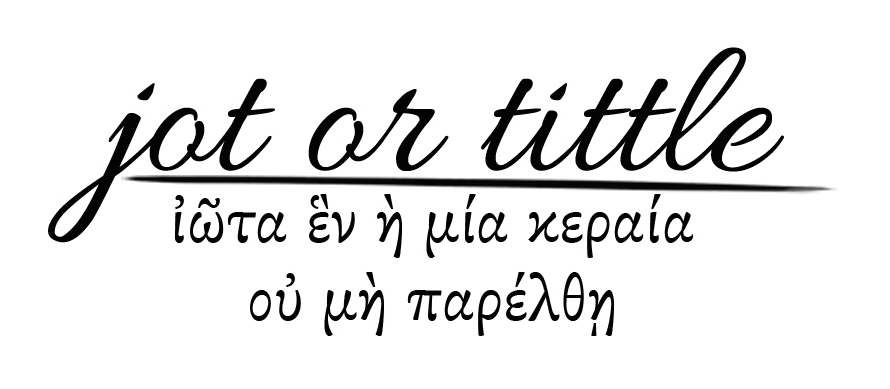

It's not that the first chapters of the Bible are unimportant to a doctrine of creation. They are vital. Rather, questions about how long ago, in how many days, or by what means God made the world “may be fascinating puzzles for some people, but answers to them do not constitute a doctrine of creation that articulates our convictions about God’s world, who this God is, how we find life, and the purpose of creation that teaches us the way of life” (vii, emphasis mine). According to Wilson, true creation doctrine has been neglected by the Western church since the eighteenth century.

“The doctrine of creation is primarily not about origin but end.”

Wilson begins by diagnosing of the symptoms of our neglecting the doctrine of creation. In the church, the result is a form of gnosticism that sees spirituality and salvation as something unassociated with the physical world and the human body. We experience a deep conflict between our “spiritual” ambitions and the clear necessity of existence and action in the physical world. Wilson proposes that the solution is a doctrine of creation that is teleological, dialectic, and trinitarian.

It is teleological because creation has its meaning only in relation to its telos—that is, its purpose—Jesus Christ the creator and redeemer: “The doctrine of creation is primarily not about origin but end” (xi, emphasis mine).

It is dialectic in its inseparable relationship to theology of redemption. The world that God created is the one that he redeems, and the world that God redeems is the one that he created. “Each has its own integrity but also only has its full significance in relation to the other” (51).

It is trinitarian in its affirmation that the one God who is Father, Son, and Spirit is its source and end, and in the necessity of considering each Person’s role (in brief: initiating, implementing, and completing) in order to have a holistic understanding of creation.

Wilson’s concerns are largely practical. He asks “What are the effects of what we believe?” It is possible to read into God’s Good World an overblown sense that a proper doctrine of creation would repair all the deficiencies of the modern church, but Wilson’s real aim is more modest than that: “A mature, robust understanding of creation is essential to growth in Christian discipleship and witness to the gospel” (viii, emphasis mine). Good creation doctrine may not be a total solution, but it is essential in our approach to the total solution, which is the good news of creation’s telos, Jesus Christ.

“A mature, robust understanding of creation is essential to growth in Christian discipleship and witness to the gospel.”

In line with his teleological reasoning, Wilson works his theological commentary on scripture in reverse, beginning with the new heavens and new earth of Revelation 21–22. Because creation and redemption are inseparable in Wilson’s understanding, he begins with the redemption of creation in which the old order is not destroyed, but “passes away” in order that creation may reach its fulfillment in its telos, Jesus Christ (134–35). Far from an escape from the material, the New Jerusalem is a “built environment” in which we are shown that “God redeems what we have done with this world and incorporates it into the new creation as God’s gift to us . . . . What is good, true and beautiful in human culture has a place in the new creation” (135–36).

Luca Signorelli's The Resurrection of the Flesh (c. 1500)

This understanding of the physicality of redemption, though certainly not new to Wilson, is one of the most provocative aspects of his work to a church that is effectively gnostic in its beliefs about creation and the afterlife. Wilson’s anecdotes about his interactions with students and conference-goers on this point illustrate the shocking nature of this claim to many in the church. For them, “Their bodies were the source of guilt and shame, and this world a terrible burden that had to be endured for a short time in order to receive the benefits of an eternity in heaven as spirit beings with the invisible God” (134). The modern church will benefit from recognizing the goodness even of the fallen creation, which God has chosen to redeem.

The teleological focus is Wilson’s greatest strength. His work avoids the fatal temptation of theology for theology’s sake by always returning the discussion to its purpose—the God who creates, sustains and redeems his creation. Wilson has not written The World or even The Good World, but rather God’s Good World, and that first possessive noun is the key to the whole work.

God’s Good World is a book that is difficult to begin. Wilson has written it in such a way that he seems to make his whole argument in each chapter, with the effect that it is a bit overwhelming at first and perhaps a little too repetitive by the end. Nevertheless it offers a take on the importance of Creation that many in the church and outside of it are desperate to hear, and which will strengthen a too-long weak point in the average Christian's theological understanding. I strongly recommend it to anyone who wonders what the Bible has to say about things like the environment, the human body, and the redemption of creation. I also strongly recommend it to anyone who is fatigued by public debates about the age of the earth. Wilson’s teaching will be refreshing and edifying.