You Can Be Perfect: Kingdom Ethics and Matthew 5:48

Carl Heinrich Bloch's Sermon on the Mount.

Christian ethicist David Gushee has recently released the second edition of Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in a Contemporary Context, which he co-authored with Fuller professor Glen Stassen (d. 2014) in 2003. In Kingdom Ethics, Stassen and Gushee strongly oppose the tradition that interprets the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7) as a collection of “hard sayings”—that is, as sayings that are “lovely sentiments but impossible for ethically realistic practical living" (93).

Many Christians are familiar with the "hard sayings" tradition: Jesus recites something from the Law, then he explodes it into a command even more difficult to fulfill. He makes demands that can’t be satisfied in order to reveal sin, and once sinners have come under grace they are forced to find some other, more realistic ethic to actually live by. It is illustrated, if nowhere else, in popular televised evangelistic approaches.

This tradition turns the Sermon on the Mount into a kind of harmatological deflation: small sins take on huge values in God’s economy. At the center of this logic is Matthew 5:48: “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (NRSV). Anyone who falls short of perfection is in danger of hell, and everyone falls short of it. Christians look forward to a time in heaven when Jesus’s paradisiacal ideals might be realized, but for now they live in God’s grace by some other, more plausible, means.

But Stassen and Gushee think that we should take Jesus seriously when he tells his audience that they must not only hear his words, but also obey them: “And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not act on them will be like a foolish man who built his house on sand” (Matthew 7:26; see vv. 16-27). Jesus’s words, according to the two ethicists, are not impossible demands. They follow a three-part pattern of traditional righteousness (“You shall not murder”), sinful patterns (“If you are angry with your brother . . . . If you say ‘you fool’”), and transforming initiatives (“Leave your gift . . . go . . . be reconciled . . . come to terms quickly”) (95–96). Rather than intensifying the Law to something unattainable, Jesus suggests realistic, if sometimes surprising, solutions. What Jesus teaches he intends his followers to do—even including his command to be perfect.

(NB: The evangelical axiom that only God is holy and that human beings depend on his grace to enter heaven is not at all in dispute in this blog post. Matthew 5:48 is hardly the only basis for this concept, and certainly not the best. Malcolm Muggeridge justly called human sin "the most empirically verifiable reality." I do not dispute that, nor that humans need God's grace. I only intend to discuss what is the most appropriate approach to one particular verse in light of Stassen and Gushee's work.)

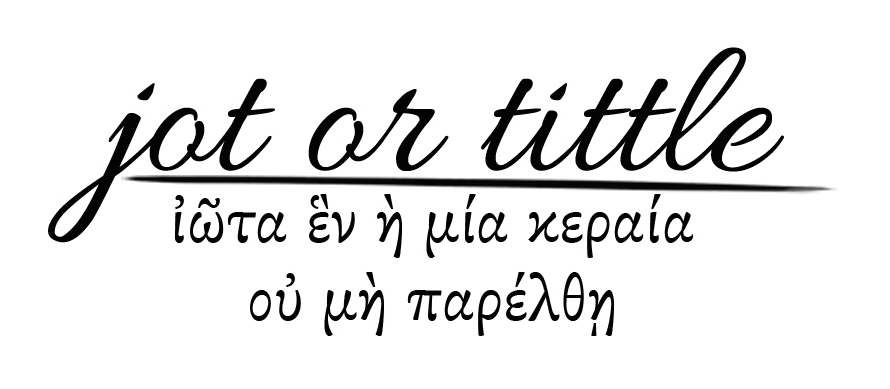

Behind Jesus's command to be perfect is the adjective teleios. Teleios is the Greek equivalent of the English “perfect,” but it can also communicate completeness and maturity. Our first reaction as English speakers in the twenty-first century is to understand the perfection in question as ontological: God is a perfect being, and his demand on us is that we also be perfect beings. This is not a Hebrew way of thinking. William Davies and Dale Allison, in their commentary on Matthew, note that God is not called “perfect” at any point in the Old Testament or in the Dead Sea Scrolls (563). For Jesus to call God perfect in the sense in which we typically understand the word would be a strange novelty in a first-century Jewish context.

In addition to Davies and Allison's observation, Stassen and Gushee offer two strong arguments for an understanding of Jesus's words that sheds the idea of moral-ideal perfection. First is a consideration of the context of Jesus’s statement. Directly before commanding his audience to be perfect, Jesus had been teaching about love for enemies:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous. For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers and sisters, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” (Matthew 5:43–48)

The "therefore" (oun) demands that we understand the command to be perfect in light of the preceding material. For Jesus to go suddenly from a discussion about loving enemies to a command to be ideally perfect is difficult to make sense of. Rethinking the meaning of teleios helps us maintain the continuity of thought.

Jesus goes out of context while preaching on the mountain.

Second is a comparison to the parallel passage in Luke 6:35–36: “But love your enemies, do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return. Your reward will be great, and you will be children of the Most High; for he is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful.” Here Jesus does not suggest that we imitate God's being. He asks that we imitate the extent of God's mercy. There is no question of being ideally perfect.

Thus Stassen and Gushee’s paraphrase: “Be complete or all-inclusive as your heavenly father is complete or all-inclusive” (122). The command to “be perfect” is not merely a judgment on us in our imperfection; it is a mandate to—like God—love even those who would do not love us. As Davies and Allison point out, "The emphasis is upon God's deeds, not his nature" (563). We are to be teleios in the sense of fullness of love–or, perhaps, moral maturity–not in the sense of ideal perfection.

“Love of unrestrained compass lacks for nothing. It is catholic, all-inclusive. It is perfect.”

Jesus’s command to love even our enemies is not an easy one, but it is one that he intended us to obey. Hate is a short but fatal step from the straight and narrow path that Jesus models. It is all too easy to go from opposing someone’s evil deeds and praying for their repentance to hating them and wishing them ill. It is all too easy to justify our hatred. It is all too easy to disguise it as righteousness.

We might learn something by following intertextual lines to another sounding of teleios in the New Testament: “Anyone who makes no mistakes in speaking is perfect” (James 3:2). Hatred harbored in our heart is quick to reveal itself in our words. “But what comes out of the mouth proceeds from the heart, and this is what defiles” (Matthew 15:18). The way we speak to and of our enemies and the way we pray for and about them is the first sign of whether we love or hate them. The way we write about them—the words we choose——reveals and sometimes even shapes our hearts. Words are not always unambiguous. Jesus spoke harshly of many people, and he was not patient with faithless leadership. Loving our enemies does not mean believing or acting as if they do no wrong. But sometimes our words are unambiguous.

Difficult as it may be, love for enemies is an ethic that Christians can and must practice. In the only other instance of teleios in the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus tells a wealthy man that he lacks one thing: “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor” (Matthew 19:21). The wealthy man does not, and Jesus observes that it is as good as impossible for a wealthy man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. “Then who can be saved?” his shocked disciples ask. His answer to them is relevant to those who would seek to be perfect in love: “With people this is impossible, but with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26 NASB).